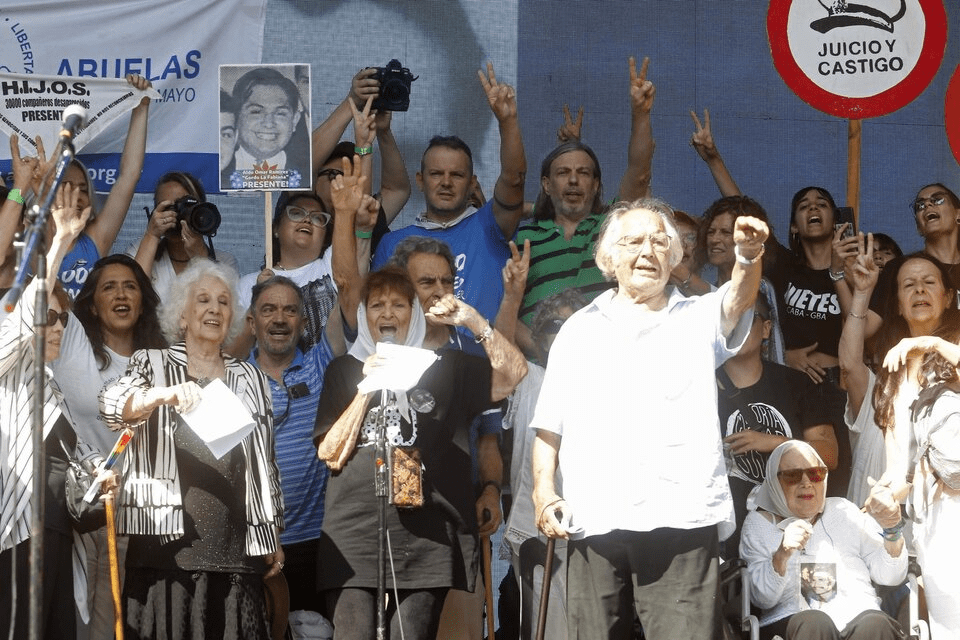

Wim Cuyvers set up twenty tents overnight on the cemetery in Rozebeke, a subdistrict of Zwalm, within the pattern of the surrounding gravestones and at the same time showing absolute respect for the latest graves. This was part of ‘Art and Zwalm 2007’, and was an extremely serious response to the organisers’ assignment: to transcend the boundaries of the artistic and examine the relationships between art and the local social, economic and geographical situation. The tents provide shelter for the chance passer-by, in what Cuyvers calls perhaps the last public place in the urban landscape as we know it in Belgium. The cemetery is one of those rare places which are today still able to preserve themselves from the usual claims on space that originate from private interests. This is only logical, since, as the ‘place of loss’ – loss of time, power, means – there is nothing to be gained in a cemetery. This exceptional lack of economic pressure makes the cemetery the perfect place to enable a form of communication that is not driven by trends or interests, but rather questions existence itself.

Innocent as this intervention may seem, the local inhabitants turned out not to be particularly pleased with this sudden activity in the cemetery and even less with the virtual possibility of lodging there. No one listened to the arguments of a few passers-by that the extra tent space provided an excellent opportunity to reflect on the thin line between life and death, and in the future even to organise scouting activities there. This intervention was dismissed as a violation of the holy nature of the cemetery and as showing a distressing lack of respect for the repose of the dead. The national media eagerly picked up on this local upset and soon played it out in terms of cultural awareness. While the rural inhabitants were portrayed as having no sense of the human, poetic nature of the intervention, Cuyvers was shown up as the man who, in the name of art, would not submit to the will of the people. However, in all this it was deliberately forgotton that Cuyvers had emphasised several times that setting up tents in the cemetery may well have been done as part of an art biennale, but that apart from that it had nothing whatsoever to do with art. It was above all a reflection on the state of public space in Belgium, and Zwalm in particular: buried under road signs, speed ramps, route signs and boundary enclosures of all sorts – which not even an art route could avoid. It is this spatial choreography of the Zwalm area that Cuyvers saw as an enlargement of the ultimate capitalist vision of public space. It is a circulation space without conflict, risk or transgression in which one is only permitted to stop for the purposes of consumption and the entry into self-created, private detention centres.

It is as part of this sort of specific choreography that the tents in the cemetery create a space where there is the mental possibility of ‘being’ in Zwalm without being directly led by one or other instruction. Cuyvers thereby gives his own twist to the tent campaigns in French cities that give visual form to the right of the homeless to accommodation – from which he clearly drew his inspiration. The intervention in the cemetery makes it clear that today it is above all a question of demanding the right to withdraw from the daily pressure to consume, circulate and capsulise and claim the right to lodge in the public space with no obvious intention. In short, this intervention shows – perhaps despite Cuyvers – that the public space is only in theory an untouched, pure piece of land, and in practice soon becomes the object of obscure manipulation and calculation, and must rightly be won and defended.

Gideon Boie

Article from The Architectural Yearbook 2006-2007 (edition 2008) published by Flemisch Architecture Institute (VAi). See also: http://www.bavo.biz/texts/view/211