Het domineert de internationale voorpagina’s niet meer zoals een aantal weken geleden, maar de Catalaanse onafhankelijkheidsstrijd heeft een nieuw hoogtepunt bereikt in haar confrontatie met de Spaanse staat. In België is het vooral de separatistische N-VA die ondubbelzinnig steun heeft uitgesproken. Maar naast het bekende feit dat in Catalonië de beweging eerder links is, is de strategie van de Catalanen ook sterk verschillend van de Vlamingen. Ik vroeg iemand uit de beweging wat hij de buitenwereld graag zou uitleggen.

Het heeft uiteindelijk geleid tot een lang artikel dat de strategie bespreekt en situeert in een historisch kader. Dit publiceer ik nu. Er volgt nog een bespreking met follow-up vragen.

Where we are now

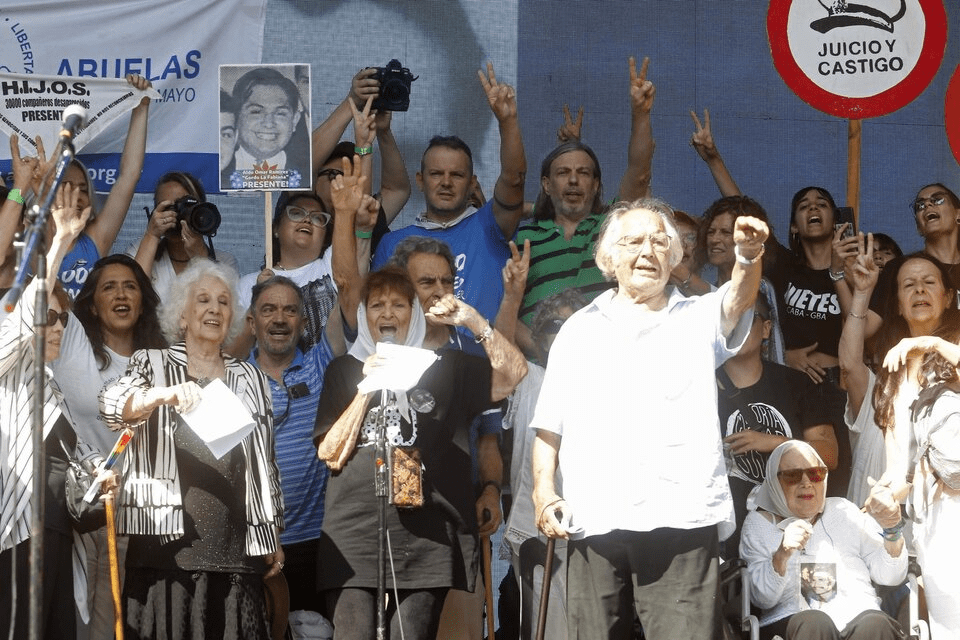

The political crisis of the Spanish State and Catalonia has risen to the front pages of the general media of Europe during the last month due to a series of events which started with the shocking images of police repression towards the voters of all ages and conditions of a Catalonia independence referendum on the 1st of October.

This ominous day has been followed by periodic strikes, demonstrations of both supporters of the independence and unionists, two official declarations of independence by the government of Catalonia (the Generalitat), the direct intervention of the central Spanish government of the autonomy of Catalonia, the preemptive imprisonment of the leaders of the two main civil organisations promoting independence, the mandatory dissolution of the Catalan Parliament and the convocation of Catalan elections for the 21st of December.

It is indeed a trail of demonstrations of force, popular wills and implacable State repression which has recently escalated to the preemptive imprisonment of almost all of the Catalan government chief officers and the issuing of a European arrest warrant against the suspended Catalan President Carles Puigdemont whom flighted to Belgium.

In light of such series of events charged with historical gravitas -which I think are far from being over- I think it may be welcome to offer a personal perspective on the matter as a left-wing young Catalan economist and addressed to European readers of all ages and backgrounds.

I think it may be worthy because I have noticed periodically that people from outside Catalonia -regardless of political orientation or education- usually do not grasp well -justifiably, because it requires a lot of weekly attention- the intents of pro-independence parties and actors and how events in previous years have unfolded so as to reach such a state nowadays.

To be blunt, what I think causes the most confusion is the unfamiliarity with the strategy of pro-independence forces, which is mainly a strategy based on outfoxing the Spanish central government but without the intent to really question its hegemony besides popular demonstrations and political actions seeking symbolic effects.

The strategy of the separatist forces is to expose the Spanish state as a repressive institution

Such “modest” strategy in its aim -to call it somehow- is due to the impossibility within the present Spanish statu quo to make constitutional reforms which could reasonably give an answer to independentist advocates on the one hand, and on the other, the lack of effective power to unilaterally declare independence and to make Catalonia a sovereign State able to start its path among the States of the international community.

Introduction to the crisis of the Regime of 78

It is possible to fit the Catalan crisis within a broader context of crisis of the Spanish political consensus and balance of forces since the onset of the economic crisis in 2008. The crisis of the order which has been labelled as “The Regime of 78” (in allusion to the Spanish Constitution of 1978 which established the legal basis from which the post-Franco State would be construed).

The economic crisis has been more severe than the Great Depression

This economic crisis (more severe and protracted than the effects that the Great Depression had in Spain in the 1930s) had his initial political consequences through a crisis of approval of the PSOE’s government and of President Zapatero’s management of the crisis, which in turn, led to a change of government in 2011 through a landslide victory of the Partido Popular (PP) in the 2011 general elections.

The PP’s austerity policies and deregulating efforts and the deepening of the crisis generated the emergence not only of a renewed independentist movement from 2011 onwards, but also the emergence of two new major political parties since 2014, Podemos and Ciudadanos, which decisively evidenced that the consensus of 78 and the unchallenged bipartidism between PSOE and PP since 1982 was crumbling and will probably never be the same again.

The old “Catalan problem”

It is necessary to state that the Catalan independentist movement as a modern political movement is much older than the Regime of 78 and the golden era of bipartidism, being about a hundred years old. It is not born out of the current Spanish political crisis.

The first independentist political party Estat Català (Catalan State) was founded in 1922 and the roots of modern Catalan nationalism can be traced back to the second half of the XIXth century to the Renaixença (Catalan Renaissance) cultural movement. A movement which sought to revive the Catalan language, literature and arts and which can be easily related to the romantic and nationalist movements that had been previously developing in Europe during the XIXth century.

Moreover, it is not the first time in History that independentist parties have come to power in Catalonia, reached a social majority, and the Catalan government has declared an independent Catalan Republic. During the time of the Second Spanish Republic (1931-1939), Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (Republican Left of Catalonia, the same political party which is nowadays instrumental in the independentist movement) with Presidents Francesc Macià and afterwards Lluis Companys at the head, declared Catalan independence in 1931 and 1934 respectively.

Macià was forced to back out and Companys (along with his cabinet) was imprisoned for such acts by the Spanish executive, which was under the control of a coalition of conservative Spanish forces from 1933 to 1936. This was a regressive and very socially convulse period in history of rollbacks of the initial progressive policies of the Republic which left-wing Spanish political parties had implemented with mixed success.

The Catalan independence has been declared before, in 1931 and 1934

Back in the day, in the same fashion of today, the Catalan independentist movement exacerbated the political crisis of Spain from an initial major economic crisis and prompted backlashes from the Spanish government and conservative Spanish parties.

The social and national issues that the Second Republic had to face were ultimately not able to be dealt within the confines of the Republic’s institutional and legal attributions, since the insurrection of fascist generals within the Spanish army and the bad management of the situation by the Republican government led the Republic to become a failed State by the end of 1936.

The Spanish dictatorship and post-Franco Spain: The Regime of 78

The fascist military forces led by the general Francisco Franco – decisively aided by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy- triumphed over the popular army of the Spanish Republic by 1939 and submerged Spain into a dark age of material misery and relentless political repression towards progressive forces and peripheral nationalisms which disarticulated them to a great degree.

The Spanish dictatorship aligned itself with the Axis powers in WWII although it was a non-belligerent country and applied autarkic economic policies in the line of the Nazi and Fascist States. After their defeat, Spain willingly isolated itself from foreign influence and continued with its autarkic economic policies well into the second half of the 1950s.

After almost 20 years of incredibly damaging economic autarkic policies, endemic corruption and mismanagement, the Spanish government engaged in a major shift of economic policy, from autarky to commercial openness and more market-oriented policies.

It began to reintegrate within the European economy from the 1960’s onwards and began a period of remarkable economic convergence with the countries of the European Economic Community. Within the European international division of labour, the Spanish economy had as its motors of economic development tourism, real estate construction and cheap manufacturing labour.

It is an orientation of the economy which has not changed much since the 1960’s. In its moments of greatest income catching up, Spain was even more dependent upon real estate construction and tourism, hampering through a dutch disease the manufacturing sector and other more advanced service and manufacturing sectors. The crisis and its bad management have had as its effect a temporal decline of real estate construction and boosting tourism and the manufacturing exports sector through an internal devaluation and a deregulation of the labour market.

Rapid GDP growth and catching up through these policies made the Spanish dictatorship realise its positive impact and seek greater levels of integration within the European economy to satisfy the needs of private and State capital accumulation. Talks between Spain and the EEC for a future adhesion of Spain began already in 1962 and in 1970 the Spanish State would sign a preferential trade agreement with the EEC.

The end of Franco was a regime change by which Spanish capital could integrate within the EEC project and the heirs of the dictatorship could sleep at night without any fear of being persecuted and condemned

However the pivotal problem for Spain was that it was not a representative democracy like its EEC counterparts and could not formally join without a regime change. This fact coupled with a more peaceful social statu quo and the old age of Franco started to make capital forces in favour of a “Europeanisation” of Spain in the late 1960’s and the 1970’s and to look sympathetically at a peaceful regime change towards a European representative democracy in order to gain the economic benefits that a higher integration represented.

After the death of Franco in 1975, a transitory period began which saw major political and social upheaval coupled by a worsening macroeconomic situation in Spain. The transition culminated after 4 years with the general elections of 1979, after a new constitution in 1978 was accorded and ratified through referendum and an 88% of affirmative votes.

It represented a clear example of what Gramsci called “passive revolution”. It consisted basically on a regime change by which Spanish capital could integrate within the EEC project and the heirs of the dictatorship could sleep at night without any fear of being persecuted and condemned and losing their wealth and influence. But all this at the cost of having to accept much more strength and rights by labour forces and progressive parties and a decentralization of the State with new statutes of autonomy to Spanish communities.

Barring the failed coup d’État of 1981, the new representative democratic regime proved to be very solid and able to create a stable political consensus which has lasted well up until the 2010’s though having to endure long processes of economic and labour reforms to culminate into the accession of Spain into the EEC in 1986.

The new “Catalan problem”

Catalonia gained autonomy on several competences through the Statute of Catalonia of 1979 and were gradually increased over the course of the years up until the 2000’s (public education, public health service, autonomous police force Mossos d’Esquadra, competences in roads, railroads, public works, culture, etc.), also a differentiated Catalan civil code was designed and approved.

The Catalan citizens approved the Constitution of 1979 by a large majority, as a text which signified very substantial improvements in social and self-government matters (without thinking it would become a corset later on) and for more than 20 years the political landscape seemed very stable with the Catalan conservative CIU party uninterrupted rule. This party emphasised a strategy of autonomism and gradual modest gains in self-government, which were usually achieved by offering political support to Spanish governments of different sign in return of increased competences and fiscal resources to fund them.

In 2003 a tripartite coalition of progressive parties in Catalonia (PSC which is the PSOE’s Catalan section, ERC and ICV) reached power in Catalonia and coupled high increases in social spending with regard to the previous CIU governments and set in the design of a new Statute of Autonomy for Catalonia.

The final text of the Statute was cut back from its initial aims (in fiscal competences, the definition of Catalonia as a nation, limitations on judicial matters, etc.) before being approved by the Spanish legislative but was still nonetheless roundly approved by Catalan voters in referendum in 2006.

In 2010, with the economic crisis already underway, the Spanish Constitutional Court declared unconstitutional several articles of the approved text and put emphasis on the judicial ineffectiveness of the concept of Catalonia as a nation.

The whole process and the reaction towards the Statute of the most reactionary segments of the Spanish population and political forces (which included the PP and a sizeable share of the PSOE) exacerbated the feeling that the Catalan aspirations and the open hand which had been extended to the Spanish State had been mistreated

The tripartite government fell in the 2010 Catalan elections and CIU regained executive power in Catalonia. It faced an unprecedented fiscal deficit as a result of the crisis and the sharp loss of revenues. To contain in it, it engaged in policies of austerity and privatisation of public property, which was compounded by an increase of the fiscal transfers that Catalonia had to make to other parts of Spain even more affected by the crisis. This led the CIU government to attempt a fiscal pact with the Spanish State like that of the Basque Country by which the finance of the Generalitat, which the Spanish government categorically rejected because it would mean a substantial loss of fiscal revenues in a time of crisis.

Between 2006 and 2017, the estimated support for the political option of Catalonia as an independent State has skyrocketed from a 14% share to more than 48%

Both elements, a battering of the aspirations of Catalan self-government and a profound economic crisis poorly managed and its massive social costs spurred a very rapid surge of Catalan citizens in favour of independence and the possibilities that a new State could have both in the national and in the economic front.

In march 2016, President Artur Mas stepped down so that the single list alliance between CIU and ERC (Junts pel Sí) could have the vital support of the CUP (a left-wing pro-independence party) and be able to form a new government with President Carles Puigdemont at the head.

Between 2006 and 2017, the estimated support for the political option of Catalonia as an independent State has skyrocketed from a 14% share to more than 48% of the citizens according to the Centre d’Estudis d’Opinió (a public Catalan center of social surveys) , which represents a bigger share of those against it (40%) with the undecided and the equidistant representing around a 10-11%.

The independentist strategy

Although having won such spectacular popular support in such a short period of time, this popular support in favour of Catalan independence has had to confront the power of the crumbling but yet still very strong Spanish consensuses and the repressive force of the Regime of 78.

The strategy has had to consist essentially (with varying intensity, changes of leadership and from a more right-wing to a more left-wing view) on making the State reveal itself as the neurotic and implacably repressive machine it is against political parties and actors fundamentally opposed to the order established by the Constitution of 1978, both peripheral nationalists and left-wing opposers.

The aim is to generate popular rejection within Catalonia and Spain by showing what the Spanish State is really about (the preservation of this post-Franco conception of Spain and a subjugation of labour forces to the needs of capital through different mechanisms, chiefly the European Monetary Union). The aims is to make international actors question the Spanish State, to put both inside and outside pressure onto it so as to force it in the future to major redesign, weaken the PP, and -barring more rupturist future developments- allow Catalonia to ultimately hold a referendum in accordance with a renewed Spanish legislation.

The strategy is this one mainly because the central State has absolutely all the legal and repressive tools at his disposal and the PP, Ciudadanos and PSOE are relentless enough to not tremble at all if they strip Catalonia of its self-government. The vicepresident of the Senate has already stated that if in the elections of the 21st of December pro-independence forces win and they keep pursuing attempts at independence, they will intervene Catalonia’s self government again (and in all likelihood keep Catalonia in a State of permanent intervention if the winning parties advocate for the independence of Catalonia).

The problem and the impasse between Catalonia and Spain strides in that a Catalan unilateral independence would not be durable because of the repressive strength of the Spanish State to enforce its constitutional order and in that the reform of the Spanish Constitution should have to follow an aggravated reform procedure. Such reform procedure implies PP, Ciudadanos and PSOE would have to face a political downfall of biblical proportions or make hard to imagine political twists, since such reform would have to be approved by a majority of two thirds of the Spanish Senate.

Some European friends of mine have been interested in knowing whether an armed conflict is likely, and I think that it is extremely unlikely to happen. I think it is safe to say that for an armed conflict to happen there should be way more instability, generated by, for example, a new major economic crisis in Spain and the Eurozone.

One of the main reasons is that there are no factions within the military that would defend the new independent State, simply as that. It is one of the most unified institutions against secessionism. Furthermore, the autonomous Catalan police force, besides being divided itself, is no match for an open confrontation against central government police and armed forces.

What is most concerning is the eventuality that PP and Ciudadanos (and maybe PSOE depending on the balance of power in the Spanish legislative) ultimately choose to outlaw or substantially limit pro-independence parties through legal mechanisms like the Ley de Partidos, (a law by which for example numerous basque political parties were systematically forbidden through the argument of having relation with basque pro-independence terrorist group ETA).

Conclusion

Having illustrated all these points and as a conclusion, I think it is essential that the independentist movement keeps actively seeking confrontation against the Spanish State with a lot of intelligence in order to constantly make very visible and fresh its structural violence in the eyes of Catalans, Spaniards and Europeans.

I firmly think that highlighting the biggest violences and contradictions of social systems, even upon oneself, is up to some limit indispensable. Those who endure more structural violence than they reproduce can make others aware of it and develop the willingness and the intelligence to overcome it.

Bernat Aritz Monge Nunes