In light of the urgencies of the present times, in light of the Anthropocene, the age where Man’s ecological footprint can be read into the geological layers of our planet (for it is geologists who came up with the term Anthropocene) and has become so big it is destroying his entire habitat and is causing unimaginable suffering to both humans and nonhumans, discussing civil disobedience is not an academic exercise. In fact we could devote this entire lecture to it, and spend our precious time together with looking at practices of contemporary civil disobedience: from the squatting of Hotel Central in Brussels in the early nineties (in which I was involved) to actions like Picnic the Streets (was there), cyclo guerilla (done that, well more as a tourist), grand-scale cases like le ZAD in France (zone à défendre – a whole and quite long story in itself, the airport at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, remember….) We should also look into the Potato War (de Aardappeloorlog in Wetteren) and the sacking of Barbara Van Dyck (I was involved in that too and have also written quite a bit about it). Not to forget, maybe the best example, in a sense, the climate strikers: the Great Greta Thunberg, Anuna De Wever and all those impressive flocks of adolescents. Skipping school to do something children are not supposed to do (as they have no voice, no vote): politics. Or think of Extinction Rebellion! Fabulous case of civil Disobedience: entering Parliaments, occupying squares, chaining themselves to the Palaces of Politics. And then there is art and activism, my God. Don’t get me started (let’s save this for the discussion. See my theses on art and activism in the Age of Globalisation, online).

But, all of that I consider rather your homework (if we find the time we could have a look at all these cases briefly), I for one – asked to give a lecture on disobedience to young artists (in the frame of this LABO Summerschool of Champ d’Action at DeSingel) – I cannot but start to build a philosophy of disobedience. So let’s start from scratch. (That is the repulsive impulse of philosophy and the tic nerveux of philosophers, nothing to do about it).

A plea for obedience

Obedience is the basis of anthropogenesis, or in other words: obedience is the basis of education. Disobient children are hopeless, even for themselves. Obedience is crucial for children to learn that they are not the center of the world. Furthermore, it teaches respect, self-discipline, perseverance, sense of duty, and all that… It is the possibility to listen to a call that breaks open the chaos of immediate libido. To listen is the essence of obedience. It is clearly spelled out in the Dutch word ‘gehoorzaamheid’. It means the capacity to lend your ear. Children who don’t listen (to orders) cannot hear the inner voice of discipline and respect, and hence have no discipline, and mostly no respect. And without respect no self-respect.

So, I think obedience is a very important thing to learn. Children who cannot obey are a plague for their parents, teachers and to themselves, for they are doomed to a sort of tyrannical anarchy. It is the magic of Mary Poppins that she can make the spoiled and bored children of the banker obey by her combination of authority and wonder, discipline and tricks. ‘In every job that must be done there is an element of fun.’ But ‘a spoonful of sugar makes the medicine go down’. The possibility to hear and to listen to the appeal or command from the Other is important to become human. Hence my somewhat pompous opening phrase: obedience is the basis of anthropogenesis.

Of course, one could argue that education is about the opposite: emancipation. in his lecture on Enlightement immanuel Kant called on people not to listen to the general, the priest, the teacher, but to think for themselves. ‘Dare to think’. So, opvoeding tot mondigheid (to salute Adorno) ‘education of empowerment’, is linked to the mouth (‘mondigheid’), as obedience (gehoorzaamheid) is link to the ear…. An empowering education has to teach self-organization, autonomy, self-reliance, personal and moral strength, whatever… That is true. But I would argue that they badly need their dialectical opponent of interiorized obedience and self-discipline. The tension between emancipation and obedience, between ear and mouth, is crucial in the correct guidance and in that dialectic resides precisely the challenge of all upbringing and education. It almost reflects in a micropolitical way the discussion on anarchism versus the well-organized state. (Or more playfully: big mouth need also sharp ears.)

Psycho-analysis has understood this well. The conscience is according to Freud the interiorization of the voices that we had to obey, the super ego is nothing else than this interiorized moral voices, this conscience. Freud uses them as synonyms at some point (in his text on narcissism*): super ego or conscience. So a person who cannot listen to these compelling inner voices, has no conscience, is as we say without conscience, ‘gewetenloos’: unscrupulous, honor-less. Bad. This moment or movement away from whim and the discovery of moral law by the interiorization of social conventions and commandments, Lacan has called ‘the name of the father’. The symbolic order breaks open the dual relationship of mother and child in the imaginary, the father brings the moral law into this duality, as a schism that opens up to the big other. (This is a role not a gender!)

So, to make a long story short, you will not hear from me any glorification of disobedience per se. Obedience and conscience are totally crucial in the process of anthropogenesis, the difficult, impossible and never-ending process of becoming human. But we are not here to moralize nor to dig into the process of methods of how to educate children but to think philosophically about disobedience. We will however discover further down, that this obedience to conscience is the basis of all civil disobedience, at least: it is the basis of it according to the founding text of Thoreau. All civil disobedience is a higher a higher instance, to inner conscience instead of outer laws.

Obediency as school of faith

Obedience, submission is a deep affect in man, you could say it is the essence of religion: submission to the gods, to the god, to the ancestors, to destiny, to fate. All or at least most people have a tendency towards religious, political or even sectarian obedience or submission to a faith. Faith is an obedience. Obediency is the word in Dutch for a ‘loge’, a ‘lodge’, or sect within free masonry. More generally, it is used to designate somebody’s allegiance to a school of thought, something you are loyal to, but it could be very useful for any thought on obedience, any philosophy of disobedience. The French language makes even a clear distinction: obeissance and obedience. This word does not exist in this meaning in English (according to all the online dictionnaries we consulted), I hereby would propose to introduce obediency as the faith or school to which you obey and belong, as a new meaning of the word in the English language.

This new concept so to speak gives us an interesting entry into many matters, amongst others into the nature of philosophy itself. But before we go into this, let’s taste the glorious almost vicious cruelty of the concept. When you say that someone is of Marxist obediency, you immediately make clear that the person maybe should start to think autonomously instead of obeying to somebody else’s thoughts. It is thus a concept that points towards this subordination or submission that is typical for people who belong to a belief, hence, it is always suggesting some sectarian leanings. And that brings us to philosophy.

Philosophy is a dis-obediency, a exercise in methodic disobedience, a suspension of beliefs, an ‘insubmission’ (insoumision in French) – another nonexistent word, which points to a sort of rebellious, unruly, recalcitrant and contumacious spirit. You could say this is the essence of philosophy: the critique of belief systems and obediencies. Hence, the trial of Socrates, Spinoza being expelled from his Jewish community, Giordano Bruno burned at the stake, etc… Even Aristotle had to flee at a certain moment and Descartes thought it wise to hide out in Holland. Of course, this ultimate intellectual disobediency, this anti-sectarian sect, this disbelief produces new obediencies of its own right, called philosophical schools, like Marxism, Freudianism, Hegelianism, Kantianism. But each philosophical doctrine is doomed to be criticized and destroyed by the next philosophers.

It cannot be denied: philosophy has a link to religion and sectarianism. Like religion, it is trying to reveal what is the truth, how the world is made, what should be done morally and politically and what in short is the good life. So, having followers, or pupils, that is what links the philosopher to the guru, but philosophy has, in sharp contrast to any religion or sect, no holy scriptures, the concept of a holy book is profoundly anti-philosophical. In philosophy all books are holy, and none of them is particularly holy. All of them should be read and discussed openly and critically. The resistance against ‘school formation’ or sectarianism within philosophy is as strong as the tradition of philosophy itself: the antiphilosophical elements in Nietzsche and Deleuze are a witness to this.

Philosophy even has to be defended against itself. It is the intensity of the confrontation with a irreducible exteriority that has to break open every philosophy (See on this Laurent De Sutter, Que’est ce que la Pop’ philosophie). It is precisely the obedience to a higher voice, the quest of the truth, the good and of beauty, this eternal questioning and self-criticizing that drives philosophy into disobedience. Disobience then becomes a higher obediency. Hence the power of will: you cannot lock up somebody with a clear ideal. You can put his body in prison, but not his ideal. Invictus, unconquered, the motto of Nelson Mandela, and so many other disobient freedom fighters…

Mary Poppins and the climate strikers

There is also a disobedience that is a precondition for politics and it comes to Rancière to have revealed it to us. The concept of the political of the French philosopher Jacques Rancière is wonderful, but hard to comprehend. For him, the political is a moment when the natural order, in which everyone knows his/her place, is interrupted. A moment when a group that is excluded from governing demands a vote. This is accompanied by a sort of disobedience to the natural order and also a sort of misunderstanding. The goal is to undo an injustice. In that moment the new group (as a new political subject) proves the principle of equality and that is the only real meaning of democracy for Rancière. He calls everything else (just about everything that we consider to be real politics) ‘la police’, government or governance, policy and policing.

That remains abstract. To illustrate his theory I usually refer to Mary Poppins. The character Winifred Banks, the mother of the unruly children, is not only a hurtful and submissive wife, but also a suffragette. She knows very well that she is contributing to history by coming out on the street for women’s voting rights (‘our daughters’ daughters will adore us,’ she sings). Winifred is part of a new political subject, that is obvious. She literally demands a voice and wants to undo an injustice (le tort): that women are only halfwits, in political terms minors, not adults. There is also a misunderstanding (la mésentente): the banker with the bowler hat has no idea or thinks it is all quatsch. And the natural order is broken: the woman at the hearth, the man at work. It’s all in there.

To make it even more graphic I would like to refer to Mary Richardson, who in 1914 vandalized the Rokeby Venus of Velázquez in the National Gallery. I find this act of political vandalism impressive, even if it hurts me a bit as an art historian, if you google the painting you will see how graphic her vandalism is: that carving in that painting, in that body. In these carves, you see the radicality of the suffragette movement embodied, so to speak: how she approached that naked female body to address the eternal aestheticization and eroticization of women and to give a voice to female anger about it. With her crime, Mary Richardson abolished the eternal ‘sois belle et tais-toi’.

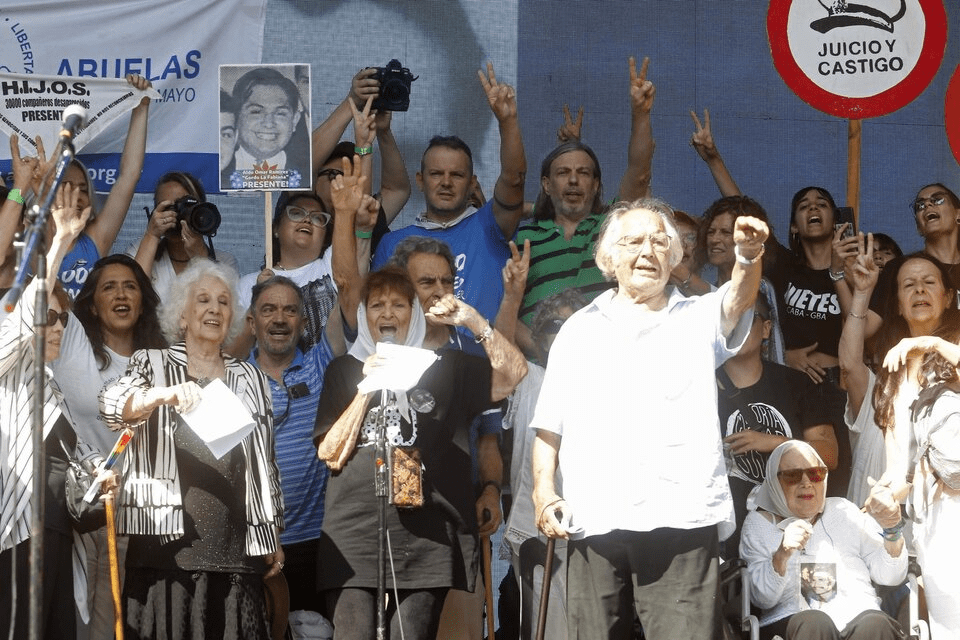

Needless to say that the suffragettes were queens and princesses of civil disobedience, of transgression of the law, quite aggressive transgression of the law even, to open up the law to a new political emancipation, to make politics more equal, more democratic and therefore better. Just like Winnifred Banks was totally double-faced, at home an obedient subservient housewife, in the streets a combative vociferous feminist. Rancière speaks about this disobedience, albeit in an indirect way when he says that the coming into existence of a new political subject presupposes the breaking down of the natural order, the place where people are supposed to be in their place. (Think of women at the hearth, men in public space, hence also the pub. Women in public space? Not good: public women. Femme publique is another word for prostitute.)

There are even more recent and if possible clearer examples of this civil disobedience: Greta Thunberg, Anuna De Wever and the other climate strikers. Children who do not yet have voting rights wake us up. They break the law by not going to school, as they should. They are both the subject of debate and the bearer of new hope. They interrupt the natural order, in which minors are legally in school and children do not exist in politics, and therefore become political subjects par excellence. They point to the greatest emergency of our time: climate change. We, the adults, have been neglecting to intervene for decades to prevent ecological catastrophes. The misunderstanding? This is reflected in the dismay of right-wing politicians and opinion makers and their followers and trolls on social media. The example of Thunberg and De Wever shows us how refreshing Rancière’s concept of the political is. What a stark contrast to the wretched spectacle that party politics performs every day. As proof of equality, the lesson that Greta Thunberg gave the greats of the earth could count in Davos: ‘Our house is on fire….I don’t want your hope, I want you to panic.’ Those climate strikers, non-voters, school-age minors who skip school to raise their voices, that is a real political moment in the terms of Rancière. Let’s hope the so-called mature world listens and finally does its homework.

Civil Disobedience

The spiritual father of civil disobedience is – why did it take him so long (I hear you think) – Henry Thoreau. It is a technique of political action that is used till the present day: as said, Picknick The Streets, The patato war, and of course the climate strikers. Extinction Rebellion – I really want to join these guys – is also using this technique of civil disobedience to force politicians to do something about climate change, and to call for an ecological state of emergency. So civil disobedience is everything except an old relic of American civic culture.

Let ‘s have a look at the origins of this idea of civil disobedience. Thoreau’s pamphlet ‘The duty of civil disobedience’, written in 1849, is worth reading, for you stumble upon a sort of high moral anarchist old fashioned male, living in a world where government is barely to be tolerated and women are simply nonexistent. You can only read it with a considerable inner distance. The good news is that the argument still stands, it is a ruthless appeal to disobey a government that is too lazy to do something about slavery and makes wars that nobody wants. In that respect, the little book keeps its relevance for today.

Let’s have a closer look at his reasoning. For Henry Thoreau, it would almost be best to have no standing army and no ‘standing government’. In fact, he pleads almost for the abolishment of a standing government. In his own words: ‘The objections which have been brought against a standing army, and they are many and weighty, and deserve to prevail, may also at last be brought against a standing government.’[1] For Thoreau, the government is best when it gets out of the way.[2] In short, his definition of the government is negative, or at least extremely minimalist, in the best American frontier tradition. ‘For government is an expedient by which men would fain succeed in letting one another alone; and, as has been said, when it is most expedient, the governed are most let alone by it.’

In the text of Thoreau, it is almost undecidable whether he is an ethical activist or a sort of godfather for the extreme right antigovernment groups, like the Freeman of Montana. The civil disobedience which I always ruthlessly and universally defended, now suddenly appears to me as a very ambiguous phenomenon, because it could lead to the making of a militia against this government. Of course, Henry Thoreau was a pacifist and one of the founders of nonviolent action, but he seems to hold an almost extremist anti-government stance and appeal to almost absolutist self-reliance and sovereignty on what is right: as there are unjust laws, why should you obey them, and unethical states, why should you subject to them? It seems the old undecidable zone where extreme left idealist anarchism suddenly blurs with extreme right anarchism, or can at some point topple into it.

But in the end, he tolerates a government as a principle in itself. Albeit in a way that resistance against it is from the outset the basics civic attitude. I quote: ‘But, to speak practically and as a citizen, unlike those who call themselves no-government men, I ask for, not at once no government, but at once a better government. Let every man make known what kind of government would command his respect, and that will be one step toward obtaining it.’

It is a question of conscience, conscience is higher than law: ‘Must the citizen […], resign his conscience to the legislator? Why has every man a conscience, then? I think that we should be men first, and subjects afterward.’ This of course, is for our small philosophy of dis-obedience as a higher obediency, crucial. In fact it is the basis of civil disobedience, and also its weakness, its Achilles heel, it is a moral politics, a politics based on moral superiority, on a moral minority, on a sort of ‘one [wo]man’s action, as Thoreau going to jail for one night for not paying his taxes, or Greta Thunberg skipping school every Friday for months.

So the law is lower than conscience. That is his point, he is very explicit, almost graphic about this: ‘Unjust laws exist; shall we be content to obey them, or shall we endeavour to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded, or shall we transgress them at once?’

This anti-legal attitude is fundamental for Thoreau’s concept of civil disobedience. ‘Law never made men a whit more just; and, by means of their respect for it, even the well-disposed are daily made the agents of injustice.’ And he evokes an army of people going to war against their conscience. He calls them machines, wooden men, and the real people of conscience, who resist the state are treated like enemies.

Even if the theme of slavery, the main reason for his civil disobedience, is only seldom mentioned in the text and no arguments against it are developed, at some moment his is very clear: ‘I cannot for an instant recognize that political organization as my government which is the slave’s government also.’

In short he pleads for ‘the right of revolution; that is, the right to refuse allegiance to and to resist the government, when its tyranny or its inefficiency are great and unendurable.’ And the target of this revolution is clear : ‘This people must cease to hold slaves, and to make war on Mexico, though it cost them their existence as a people.’ His main form of civil disobedience seems to be to refuse to pay taxes, which brought him in jail at some point (a stay he describes at length in his pamphlet). According to Thoreau, the state should listen to its ‘wise minority’. What I called a moral minority just a minute ago. But again: this is the Achilles heel, politically speaking. Why? What is the right of those activists to break the law? If my super ego tells me that abortion is wrong, shall we then have the right to destroy abortion clinics, or intimidate people who commit this unspeakable deed? Ai. Difficult. I have no solution to that.

Civil disobedience is not always right, it is a method of action and it can be despicable. Especially when it turns into a sort of terrorism. That could save us, in a final analysis to make a difference between good and bad civil disobedience, between left and right: non violence, is and remains the basis of civil disobedience. With the Gillets jaunes this line sometimes got blurred. However, let’s consider civil disobedience here as the tool of nonviolent action and civil movements. Not that I hereby condemn all violence, decolonisation struggle is a sort of warfare, but that is, I believe, an entirely different topic. To call armed resistence activism, I consider a misunderstanding, that can lead to sour discussions, with my Palestinian friends for instance.

That is a basis presumption of all activism and civil disobedience: it reckons on a more or less trustworthy goverment, a government that respects its own laws. This is of course not the case in many, if not most countries in the world. Thoreau for one is pleading that the government should see its civil movements and protest as a chance and not consider them a crime: ‘Why does it not cherish its wise minority? Why does it cry and resist before it is hurt? Why does it not encourage its citizens to be on the alert to point out its faults, and do better than it would have them?’ This sounds like a plea we hear these days to take civil movements serious as a partner of the government (we can think here of Straten Generaal, that really forced the city of Antwerp to change huge infrastructure works and now is part of the steering group for this Oosterweel-link).

Thoreau’s idea of this sort of civil disobedience is almost religious: ‘Action from principle,—the perception and the performance of right,—changes things and relations; it is essentially revolutionary, and does not consist wholly with anything which was. It not only divides states and churches, it divides families; aye, it divides the individual, separating the diabolical in him from the divine.’ Thoreau was a biblical man (as is clear from many passages in his book). This messianic antinomianism is the tradition he is part of, he is taking the political consequence of this theology. We will now dig into this messianism.

Messianic antinomianism

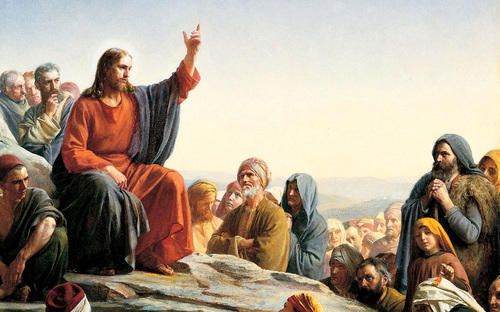

‘Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled. … Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.’ These quotes stem from Matthew, notably the Beatitudes from the Sermon on the Mount, one of the key texts of Christianity. They have been crucial to me since my early childhood. Nietzsche, Benjamin, Adorno, … Marx, and so many others have been crucial for my intellectual, moral and ethico-political formation, but these verses beat them all. Even if I am a convinced atheist, and have a very critical attitude to the church, Catholicism and even religion in general (see higher on sectarianism), I believe… I believe they contain (these words I mean), for me at least, the riddle of what much later has been called civil disobedience: to break the law, to be in jail or be persecuted for a just cause is blessed. This is of course also the real inspiration of Henri Thoreau.

The most interesting phrase – for our topic, that is – however is to be found a few lines further down than the quoted verses from the gospel in this same Sermon on the Mount, namely where Christ says these enigmatic almost ominous words: ‘I have not come to destroy the law and the prophets, I have come to fulfill them.’ (Matthew 5:17). It is worth to look into all the variations of translation of these verses[3], for they point towards a very strange relationship to the law in Christian theology or in the early Christian writings. I apologize for having to bother you with the many translations of this key quote of this lecture. ‘I have not come to destroy the law ’, also translates as: I have not come to set aside, abrogate, to make void, abolish, revoke, undo, … The second verb also has many variations. ‘I have come to fulfill them’, also translates as: I have come to accomplish their purpose, give them their full meaning, make their teachings/them come true, give them their completion.

What does this puzzling saying, statement or dictum, mean? Another one of Jesus’ proverbs could help us here, which is even better known than the ones I have quoted. It is one of Christ’s most beautiful and simple wisdoms, correcting the strict orthodox legalism of Jewish tradition and strict adherence to rituals of the mayor strands of Judaism, following the prescriptions and the teachings of the Torah, an attitude we would now call fundamentalist. It is both iconoclastic and irresistible. Then he said to them, ‘The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath.’ (Matthew 12:1-8, Mark 2:23-28 and Luke 6:1-5. ) Although early Christians were Jews, and were following the Jewish rituals, especially Christ himself, there was an inner distance towards the pharisaic literalness in the fidelity to the prescriptions. On a more political level, one should never forget that Jesus was a guru rebelling against the Roman occupation. That, of course, was the real reason for his crucifixion. He was in short a zealot. (see the magnificent book with the same title, The Zealot, of Reza Aslan.) So, his distant attitude towards the law, both moral and legal, has strong political over- or undertones.

This spirit of inner distance towards the law, one could call messianic. The true messianic moment is not so much the application of prohibitions and prescriptions but their interruption, for in the most radical form of messianic thought, redemption is a restoration of paradise. In paradise, there are no prohibitions. Paradise is a state of bliss that comes before the law, the law is meant for the fall, for the exodus, for a people that is astray, and hence needs commandments, revealed on a mount, written in stone, as long as they are infallible and iron principles. But paradise is pre-law, so redemption as the restoration of paradise is post-law. ‘Where everything is holy’, says a famous text of the Kaballah, ‘prohibitions are superfluous’. This is echoed in many Christians verses or sayings and texts, like the ones I quoted, where there is a higher instance than the law, also the moral law, and the prescriptions, namely the idea of justice. This idea is resonating until the latest writings and interviews of Derrida where he insists on the distance between the existing law and the idea of justice, the gap between any existing system of justice and the idea of justice.

In Christian tradition there is also another force that is higher than the law and that can help to fulfill it, and that is love. Where love reins, you do not need legal prescriptions. Many other holy writings of the scripture, notably in Saint Paul, point towards this messianic anti-legalism, which in academic literature is known as antinomianism (see Agamben’s superb book on Saint Paul for this, the time that remains). You could go as far as to say that messianism has an anarchistic tendency. And vice versa: that most anarchism is profoundly messianic and therefore naively hoping for an absolute break with the existing, a leap of faith, a definite break with all laws of society – and especially those of the jungle – in the here and now. The law can be transgressed in the name of justice and love. Hence Gerschom Scholem, the founder of Kabbalah studies, points out that many messianic movements ended in orgies, like Sabbateanism and Frankism.

Even in Protestantism this utopian orgiastic urge was present. In het Geuzenboek by Louis Paul Boon, there is a scene where a bunch of anabaptists take it to the streets naked as they are convinced that the truth is naked and love has nothing to hide, which proves this figure of messianic orgiastic transgression as fulfilment of the law. Do not dream of something hippy-like: they were all burned on the stake.

In fact, in Sabbateanism it was almost an official doctrine that given the fact that in redemption the Thora of the fall, the moral law since the end of paradise and the dreadful exodus, was no longer necessary as it was thought of as a restoration of paradise, the transgression of the law could be a figure of the messianic rapprochement or advancement of redemption. Maybe we should rephrase this (or even simpler, make shorter sentences). In fact, in Sabbateanism the following was almost an official doctrine: the transgression of the law could be a figure of the messianic rapprochement or advancement of redemption. How can this be? Well, the Thora of the fall, the moral law since the end of paradise and the dreadful exodus, is no longer necessary. Because it was thought of as a restoration of paradise, redemption does not know laws or prohibitions, like paradise. Therefore, the transgression of the law could be a figure of the messianic rapprochement or advancement of redemption. ‘Where everything is holy, prohibitions are superfluous.’ This most extremist theological interpretation was made up by a pupil of Sabbatai Zevi (also known as Sjabtai Tsvi), the false messiah who gave his name to this Sabbateanist sect as Sabbatai Zevi himself was forced to convert to Islam to save his skin. So, quite a transgression.

All these aspects show how deep antinomianism is and how profoundly rooted these phrases from the sermon on the mount are. I believe that this is the root of the idea of civil disobedience. What else is Thoreau’s pamphlet than an long paraphrase to the beatitude of: ‘Blessed be those who are prosecuted for justice, for to them belongs the realm of the heavens’. I told you Thoreau was a biblical man. In fact, it is amazing he does at no point refer to it (maybe he was not a real connoisseur of the Scripture, which would be amazing in itself. It is a conscious choice? But then again, why?). And then we could have an entire seminar, if not a entire course on the antinomianism in the work of Agamben, or Negri, Virno, etc, etc, etc.

In any case, if we oversee the somewhat disparate building stones, the elements of this lecture, we can see a plea for a higher obedience, one based on basic (self)discipline and conscience, a plea for the higher disobediency of philosophy and if necessary a plea for civil disobedience to break open the natural order to make place for a new political subjectivity, and finally a plea for an awareness of the deep messianic roots of it. In light of the ecological disasters that are hitting us (and those, much worse, awaiting us), in light of the Anthropocene, we might need this messianic hope. Extinction Rebellion gives an idea of this radical messianic activism, based on civil disobedience.

We did not even mention the legal action like the ‘climate cases’ in Holland, Belgium and elsewhere, it is for another lecture, to develop this contrast, but in one phrase: legal action and civil disobedience are maybe opposite at first sight, but they are on closer inspection just tools, methods of action that can be used separately or even together, Greenpeace does it all the time. So, if you have a look at the website of Extinction Rebellion now, and you overlook all the cases of activism known to you, and all those I mentioned, you can start to test somehow my humble prolegomena towards a small philosophy of disobedience. I have not come to destroy your will to activism, but to feed it. ‘Rebel Against Extinction We Must’.

Notes:

[1] https://www.ibiblio.org/ebooks/Thoreau/Civil%20Disobedience.pdf, p.3

[2] In his own words: ‘Governments show thus how successfully men can be imposed on, even impose on themselves, for their own advantage. It is excellent, we must all allow; yet this government never of itself furthered any enterprise, but by the alacrity with which it got out of its way. It does not keep the country free. It does not settle the West. It does not educate. The character inherent in the American people has done all that has been accomplished; and it would have done somewhat more, if the government had not sometimes got in its way.’ (ibid p.4)

[3] https://biblehub.com/matthew/5-17.htm