Book Review by ERWIN JANS

(published on ‘De reactor‘ in Dutch, here translated for my students, as it is the best possible introduction to the book in particular and my work in general).

The committed intellectual – Jean-Paul Sartre type – is as good as dead, said sociologist Rudi Laermans in an analysis a few years ago: ‘Hardly anyone mentions the intellectual at all anymore, unless it is precisely to denote an almost vanished human species. Insofar as there are any intellectuals left in the West, they are mainly dinosaurs or live a ghostly existence in the catacombs of society and culture. ‘ That sounds pretty bleak. Of course, according to Laermans, this does not immediately mean that all the characteristics of the intellectual would be buried along with him as a symbolic figure. But the positions that traditionally converged in his work and personality – freethinking, a value-laden engagement that often translated into an outspoken political stance, great linguistic skill, passionate essayism and public visibility – have now been disconnected.

This analysis is undoubtedly correct, yet when I think of this enumeration of qualities I spontaneously think of the person and the work of Lieven De Cauter, from his first major publications Het hiernamaals van de Kunst (The Hereafter of Art – 1991) and Archeologie van de kick (An Archaeology of Kicks – 1995) to his recent collection of essays Ending the Anthropocene (2021). De Cauter is a philosopher, art historian, lecturer at various institutions (KU Leuven, RITCS), writer and activist. In addition to his academic publications, De Cauter writes poetry (De dageraadsmens, 2000), philosophical reflections (De oorsprongen. Het boek der verbazing, 2011) and numerous opinion pieces, open letters, polemics, columns, etcetera in the traditional and digital media. His activism translates into his public commitment to the sans papiers and his support of the ecological movement. As (co)founder of the civic initiative the Brussells Tribunal – The people vs. Total War Incorporated, he openly opposed the United States military intervention in Iraq in 2003. In 2008 he was a founding member of the Platform for Freedom of Expression, which agitates against the excesses of the anti-terrorist legislation in Belgium. He was a member of the Vooruit Group and in 2011 he supported the Action Committee Barbara van Dijck, an employee of the KULeuven who participated in a protest action of the Field Liberation Movement (whereby genetically modified potato plants were destroyed in a trial field) and was therefore fired. In short: Freethinking? Check! Value-laden engagement? Check! Great language skills? Check! Passionate essay writing? Check! Public visibility? Check!

The everyday apocalypse

Ending the Anthropocene. Essays on Activism in the Age of Collapse (2021) is the concluding volume of De Cauter’s millennium trilogy, of which The Capsular Civilization. On the City in the Age of Fear (2004) is the first and Entropic Empire. On the City of Man in the Age of Disaster (2012) the second part. According to De Cauter, it all began with reading a short newspaper article from 1998 about the completion of the barbed wire fence in Ceuta and Melilla, two Spanish enclaves on Moroccan territory, to prevent illegal migrants from Africa from entering Fortress Europe. A second trigger was the death of Nigerian asylum seeker Semira Adamu in the same year. She was in a detention center near the airport and, during her forced repatriation, choked on a pillow that police officers pressed against her mouth to calm her down. Amazement is the starting point for any thinking, although in this case it is better to speak of bewilderment. Bewilderment that a society invoking the ideals of the enlightenment and identifies itself with human rights uses this kind of practice. De Cauter’s analyses stem from deep indignation. Those who read the trilogy will follow his engagement with some of the most important global and local political events of the past two decades: the 9/11 attacks, international terrorism, the war on terror, the invasion of Iraq, the construction of new dividing walls (between Israel and the Palestinian territories, between Morocco and Europe, between Mexico and the US), the commotion around the Mohammed cartoons, the 2008 financial crisis the ecological threat, the global social resistance, the Arab Spring and its failure, the war in Syria, the breakthrough of IS, the far right of politics at home and abroad, the 2008 financial crisis, the threat of ecological disaster, the coronapandemic, et cetera. In the triptych De Cauter is torn between hope and despair, between belief in the possibility of engagement and thus change on the one hand and awareness of powerlessness and unequal weapons in the confrontation on the other.

The three titles – and above all the plethora of apocalyptic terminology (fear – disaster – collapse) – make it immediately clear that De Cauter is not telling an optimistic story. Yet he emphatically resists the interpretation that he has written a prophecy of doom with his triptych. He sees his painting in strong contrasts in the first place as a stylistic device, as an ‘art of exaggeration’, to make the seriousness of the current situation clear. Was it not Adorno who wrote somewhere that only exaggeration is true? For De Cauter, the strong contrasts are a way of reading the future already in the present. We have to understand his often dramatic and apocalyptic tone as a pair of glasses to look more sharply and critically, and above all as an encouragement to take action. It is a constant search for a precarious balance to avoid two extremes: an intelligent but nightmarish theory without a possible translation into a praxis on the one hand, and a well-intentioned but loose and superficial activism without anchoring in a sober analysis on the other. In the introduction to his open-source publication De alledaagse apocalyps (The everyday apocalypse – 2011), De Cauter incidentally plays with the two meanings of the word ‘apocalypse’: ‘Apocalypse to me means more than just doom. Above all, it means revelation. Insight. Clarification. Opening. Readiness. Enlightenment. Of course. But also: Presence of mind. Alertness. Alarm. Or with Hölderlin, “Where danger grows, so does salvation”.’ It may not yet be Nietzsche’s dawn that De Cauter sees on the horizon, but the third and final volume of the trilogy is somewhat more optimistic in tone than the previous two volumes. Not because he observes an improvement in the overall situation, but because he sees more opportunities to respond and that on a global scale.

The Anthropocene

For De Cauter, the past decades are determined by three logics: the logic of capsularization, the logic of permanent catastrophe, and the logic of the New Imperial Order. The interplay and mutual reinforcement of these three logics are responsible for the current state of the world, in other words for the current political, social, economic and ecological crisis. The logic of capsularization – the encapsulation and control of urban and public space – which De Cauter elaborates penetratingly in the first part, has acquired a new relevance in these times of corona (with its bubbles, its masks, its ‘keeping a distance’ and its covid certificates). It is worthwhile rereading his essays on the dual and simultaneous dynamics of capsule and network, of mobility and limitation. The notion of “biopolitics” – the state’s concern for the lives of its people – also takes on a new urgency in these times of pandemic. Whereas in the first two volumes the emphasis was very much on the post-industrial city, on Fortress Europe and migration, on the ecology of fear, on the natural state and the state of exception (with the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben (1942-present) as the main interlocutor) on the American neoconservatives and the New World Order, on the hope that came along with the social movements and the Arab Spring and the subsequent disillusionment, the third volume focuses on the encompassing planetary theme of ecology, of which the pandemic is a part. All the other themes of the previous books continue to resonate. The triptych shows great internal coherence. It is one of the author’s merits to constantly connect this multiplicity of themes, not only theoretically but also with concrete examples and descriptions of personal activist interventions.

The ‘Anthropocene’ – the term that has become popular in recent years to designate the era in which the climate and the atmosphere experience the (negative) consequences of human activity – has become the central term in De Cauter’s closing volume and somehow seems a kind of synthesis. ‘If we want to avoid collapse, we should end the Anthropocene,’ reads the unmistakable first sentence. It contains the tension that underpins the entire book and De Cauter’s entire thinking: the deep awareness of the very concrete possibility of a catastrophe and thus of the demise of everything we hold dear on the one hand, and the equally intense will to prevent it on the other. Pessimistic in theory, optimistic in practice, is how he describes it himself. It is no coincidence that the first part of the book – Spleen of the Anthropocene – is a reflection on political melancholy. And, of course, Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) is featured here. For no other philosopher has made melancholy as fruitful for critical thinking as he has. De Cauter distinguishes between regressive, critical, and utopian nostalgia. Regressive nostalgia feeds on an idealized past, critical nostalgia uses the past to criticize the present, and utopian nostalgia is the desire for a better and just world. It is to this utopian nostalgia that we most need at this time, De Cauter says. It is somewhat reminiscent of what the Slovenian philosopher and psychoanalyst Slavoj Žižek (1949) says in his In Defense of Lost Causes (2008) about Benjamin’s “leftist melancholy. ‘In a first approach, this term cannot but appear as an oxymoron: is not a revolutionary orientation towards the future the very opposite of melancholic attachment to the past? What if, however, the future one should be faithful to is the future of the past itself, in other words, the emancipatory potential that was not realized due to the failure of the past attempts and that for this reason continues to haunt us.’

Pessimistic in theory, optimistic in practice. Utopian nostalgia. De Cauter prefers to use the paradox to describe the (im)possible position from which he thinks, writes and acts. In De oorsprongen of het boek der verbazing (The Origins or the book of amazement), he calls himself ‘a polymaniac’, a neologism which he defines as: ‘a maverick with a holy but very vague vocation’ who wanders ‘between contemplation and drive, between engagement and resignation, between politics and aesthetics, between nature and culture, between body and technology, between the social and isolation, between responsibility and frivolity, between the arts, between genres, between social roles.’

This intermediate position also translates into the form of the book. More than the other two volumes, Ending the Anthropocene is a hybrid work. In addition to a number of elaborate theoretical pieces, it also contains shorter and more directly written pieces (lectures, introductions, blogs, columns). As a reader you see the writer, thinker and activist at work. You sit with him in his office. You see him not only reflecting theoretically from a certain distance but also concretely, in the midst of events, choosing a position, reacting and addressing a specific audience. His letter to the newcomers in Brussels’ Maximilian Park, where ‘newcomers’, often undocumented people, gather, in 2018; his blogs on urbane activism in Brussels from 2014 and on the pandemic from 2020, a column defending Extinction Rebellion, et cetera: these pieces anchor the book tightly in time. They are place- and time-based interventions that show the author from his most personal, most engaged, and therefore most vulnerable side.

Ecofeminism

The end of the “anthropocene” means not only a different life practice but also a different way of thinking. This dialectic between thinking and doing is the beating heart of De Cauter’s publications. He sees the possibility of ending the ‘anthropocene’ in activism and in the further development of the concept of the ‘commons’. He subjects both movements to philosophical and historical reflection. How difficult it is to find a new unified vocabulary to describe the developments of this era becomes clear when we take a closer look at the term ‘anthropocene’. When did the “anthropocene” begin? This is hotly debated among scientists. For De Cauter, the activity of tearing open and invading the earth, of mining up resources is iconic to the anthropocene. Intervention in nature is one of the core activities of humans from the moment they become sedentary and start farming. And the more people there are on the planet, the more there is interference in nature. In this sense, the anthropocene started a long time ago and is a development in steps. The discovery of the Americas is a first major shock. The industrial revolution is the next major moment, as is the detonation of the first atomic bomb. De Cauter also does not shy away from another fact that is too often ignored in many discussions: demographic evolution. The ecological footprint of humanity as a whole is too large because there are too many of us walking around on this planet. Only after 2050 would this population growth decrease – in combination with a more ecological energy consumption and a changed consumption behavior perhaps just in time to avoid the worst?

De Cauter argues for a posthuman ecology – an ecology in which man and his exploitation of nature no longer occupy a dominant position – and sees the beginnings of this in the ecofeminism of Donna Haraway (°1944) and Rosi Braidotti (°1954), among others. It is perhaps no coincidence that Haraway speaks of the ‘Capitalocene’: after all, it is capitalism that is the foundation of the anthropocene. And of course the relationship is also made with patriarchy. What De Cauter particularly appreciates about ecofeminism is that it is at once a theory and a practice. There is also the realization that certain developments can no longer be undone and that we must learn to live with ‘contaminated diversity in degraded landscapes with displaced populations’, as De Cauter quotes the ecofeminist Anna Tsing (°1952).

Activism

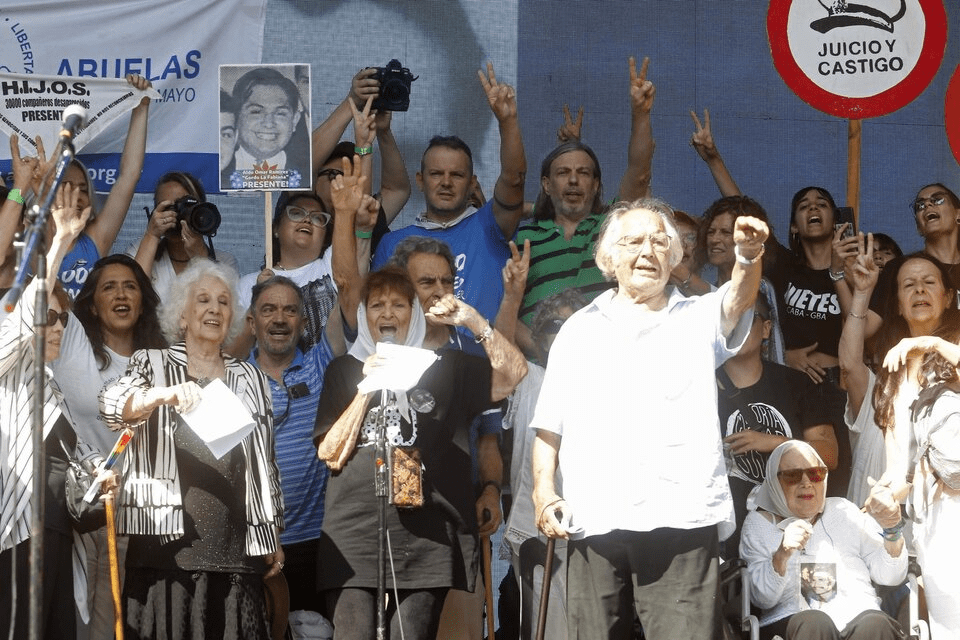

A large proportion of the essays touch on the theme of activism. One of the important questions that runs like an implicit thread through all of De Cauter’s texts is that of scale. On what scale should one think and analyze? And above all: on what scale should we intervene? And perhaps most important of all: at what scale can we do something? As individuals, as groups, as networks? De Cauter: ‘Activism is a constant interruption of normal life. Often based on the feeling of being not only responsible but the last man standing.’ * In other words, activism is not just an action, it is a lifestyle. Although De Cauter briefly touches on the theme of the ‘last man standing’ here to make the intensity of activism clear, he mainly discusses the possibilities and necessity of its collective dimension. His definition of activism as the interruption of the daily business corresponds to Jacques Rancière’s definition of politics proper: the interruption of the natural order in which everyone knows his place. It is the moment when an excluded group takes the floor. It is the moment when ‘noise’ becomes ‘voice’ and a group forms itself into a political subject. The French philosopher Jacques Rancière (°1940) considers the rest to be ‘police’, governance, politicy as we know it. For De Cauter, the future of the planet – ‘the redemption’, to quote once more the German poet Friedrich Hölderlin (1770-1843) – no longer lies in the hands of existing politics, but in the hands of what Marxist thinkers Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri have called ‘multitude’, the crowd, the anonymous ‘swarm intelligence’. Those terms, which De Cauter used in the previous volumes, are now replaced by ‘the commons’. These ‘commons’ – that which should belong to everyone – are permanently threatened by ‘the Holy Trinity of neoliberalism’: liberalization, deregulation and privatization. De Cauter relates the ‘commons’ to the concepts of ‘utopia’ and ‘heterotopia’, concepts that run like a leitmotif through his entire work because they carry within them the imagination and the energy to dare to think beyond the status quo: ‘In every activist action, in every “practice of commoning” there is a utopian spark’, says De Cauter. It is a description that brings to mind ‘the weak messianic force’ in Walter Benjamin.

De Cauters millennium trilogy is no less than a fresco in strong contrasts and many somber tones of the world in which we live. The series provides a theoretical set of instruments to capture the major forces and movements shaping our time in terms of concepts, and also does not hesitate to offer a toolkit for very concrete and local action. It is strange, in fact incomprehensible, that De Cauter’s triptych has not received more attention. After all, it does exactly what we need. It analyzes the global challenges we face, looks for major connections, for a historical interpretation and for a vocabulary.